French Anarchists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker

The origins of the modern anarchist movement lie in the events of the

The origins of the modern anarchist movement lie in the events of the

An early anarchist communist was

An early anarchist communist was

De l'être-humain mâle et femelle - Lettre à P.J. Proudhon par Joseph Déjacque

(in French) Unlike

''Anarchism''

(Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2005) . The

The

Reportedly, Michel told the court, "Since it seems that every heart that beats for freedom has no right to anything but a little slug of lead, I demand my share. If you let me live, I shall never cease to cry for vengeance." Following the 1871

The United Kingdom quickly became the last haven for political refugees, in particular anarchists, who were all conflated with the few who had engaged in bombings. Already, the First International had been founded in London in 1871, where

The United Kingdom quickly became the last haven for political refugees, in particular anarchists, who were all conflated with the few who had engaged in bombings. Already, the First International had been founded in London in 1871, where

However, at the approach of the 1910 legislative election, an Anti-Parliamentary Committee was set up and, instead of dissolving itself afterwards, became permanent under the name of Alliance communiste anarchiste (Communist Anarchist Alliance). The new organisation excluded any permanent members.

However, at the approach of the 1910 legislative election, an Anti-Parliamentary Committee was set up and, instead of dissolving itself afterwards, became permanent under the name of Alliance communiste anarchiste (Communist Anarchist Alliance). The new organisation excluded any permanent members.

From the legacy of Proudhon and Stirner there emerged a strong tradition of French individualist anarchism. An early important individualist anarchist was Anselme Bellegarrigue. He participated in the French Revolution of 1848, was author and editor of 'Anarchie, Journal de l'Ordre and Au fait ! Au fait ! Interprétation de l'idée démocratique' and wrote the important early

From the legacy of Proudhon and Stirner there emerged a strong tradition of French individualist anarchism. An early important individualist anarchist was Anselme Bellegarrigue. He participated in the French Revolution of 1848, was author and editor of 'Anarchie, Journal de l'Ordre and Au fait ! Au fait ! Interprétation de l'idée démocratique' and wrote the important early  French individualist circles had a strong sense of personal libertarianism and experimentation. Naturism and

French individualist circles had a strong sense of personal libertarianism and experimentation. Naturism and

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

, who grew up during the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

and was the first self-described anarchist. French anarchists fought in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

as volunteers in the International Brigades. According to journalist Brian Doherty, "The number of people who subscribed to the anarchist movement's many publications was in the tens of thousands in France alone."

History

The origins of the modern anarchist movement lie in the events of the

The origins of the modern anarchist movement lie in the events of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

, which the historian Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

characterized as the "open violent Rebellion, and Victory, of disimprisoned Anarchy against corrupt worn-out Authority". Immediately following the storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille (french: Prise de la Bastille ) occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, when revolutionary insurgents stormed and seized control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison known as the Bastille. At ...

, the communes of France

The () is a level of administrative divisions, administrative division in the France, French Republic. French are analogous to civil townships and incorporated municipality, municipalities in the United States and Canada, ' in Germany, ' in ...

began to organize themselves into systems of local self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

, maintaining their independence from the State and organizing unity between communes through federalist principles. Direct democracy was implemented in the local districts of each commune, with citizens coming together in general assemblies to decide on matters without any need for representation. When the National Constituent Assembly attempted to pass a law concerning the governance of the communes, the districts instantly rejected it as it had been constituted without their sanction, causing the scheme to be abandoned by its proponents.

In particular, the ''sans-culottes

The (, 'without breeches') were the common people of the lower classes in late 18th-century France, a great many of whom became radical and militant partisans of the French Revolution in response to their poor quality of life under the . T ...

'' of the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

were denounced as "anarchists" by the Girondins. The Girondin Jacques Pierre Brissot

Jacques Pierre Brissot (, 15 January 1754 – 31 October 1793), who assumed the name of de Warville (an English version of "d'Ouarville", a hamlet in the village of Lèves where his father owned property), was a leading member of the Girondins du ...

spoke at length about the need for the extermination of the "anarchists", a group that did not form any political grouping in the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nationa ...

, but nevertheless were active participants in the revolution and vocal opponents of the nascent bourgeoisie. The ''Enragés

The ''Enragés'' (French for "enraged ones") commonly known as the Ultra-radicals (french: Ultra-radicaux) were a small number of firebrands known for defending the lower class and expressing the demands of the extreme radical sans-culottes durin ...

'' were among the defenders of the ''sans-culottes'' and expressed a form of proto-socialism that advocated for the transformation of France into a directly democratic "Commune of Communes", a call later taken up by the 19th century French anarchist movement. The ''Enragés'' attacked the bourgeoisie and the representational composition of the National Convention, which they opposed in favor of the sectional assemblies.

The conflict between the Paris Commune and the National Convention escalated into a "third revolution", as an insurrection was openly championed by the ''Enragés'' led by Jean-François Varlet

Jean-François Varlet (14 July 1764 – 4 October 1837) was a leader of the Enragés faction during the French Revolution. He was important in the fall of the monarchy and the Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793.

Life

Born in Paris on ...

, who desired to overthrow the Convention and establish direct democracy throughout France. However, this attempted "revolution of anarchy" was defeated by the Girondins, partly due to a lack of support from the Jacobin Club and the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

. Nevertheless, the continuing escalation of the conflict and increasing radicalization culminated in the Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, during which the Girondins were purged from the Convention and the Montagnards

Montagnard (''of the mountain'' or ''mountain dweller'') may refer to:

* Montagnard (French Revolution), members of The Mountain (''La Montagne''), a political group during the French Revolution (1790s)

** Montagnard (1848 revolution), members of t ...

took control, centralizing power in the hands of the Committee of Public Safety and leaving the direct democratic ambitions of the ''sans-culottes'' and ''Enragés'' completely unfulfilled.

With the beginning of the Reign of Terror, the ''Enragés'' underwent a campaign of repression by the Committee, although the government also attempted to make some economic concessions in order to not alienate the ''sans-culottes''. The ''Enragés'' leader Jacques Roux

Jacques Roux (, 21 August 1752 – 10 February 1794) was a radical Roman Catholic priest who took an active role in politics during the French Revolution. He skillfully expounded the ideals of popular democracy and classless society to crowds of ...

committed suicide after being called to trial by the Revolutionary Tribunal

The Revolutionary Tribunal (french: Tribunal révolutionnaire; unofficially Popular Tribunal) was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. It eventually became one of the ...

and by 1794 the ''Enragés'' had all but disappeared from public view. The Committee subsequently began to move against sectional democracy and undertook a vast bureaucratization

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

of the state machinery, converting elected positions into ones appointed by the state and transferring power from the hands of the sectional assemblies into those of the government. The power of the ''sans-culottes'' began to wane as the Terror intensified, with the Hébertists and Dantonists also being suppressed. Eventually, the fall of Maximilien Robespierre

The Coup d'état of 9 Thermidor or the Fall of Maximilien Robespierre refers to the series of events beginning with Maximilien Robespierre's address to the National Convention on 8 Thermidor Year II (26 July 1794), his arrest the next day, and ...

brought an end to the Terror and the Thermidorian Reaction

The Thermidorian Reaction (french: Réaction thermidorienne or ''Convention thermidorienne'', "Thermidorian Convention") is the common term, in the historiography of the French Revolution, for the period between the ousting of Maximilien Robespie ...

began to rollback many of the revolutionary changes that had taken place.

The lasted vestiges of revolutionary anarchism were expressed by the Conspiracy of the Equals

The Conspiracy of the Equals (french: Conjuration des Égaux) of May 1796 was a failed coup d'Etat during the French Revolution. It was led by François-Noël Babeuf, who wanted to overthrow the Directory and replace it with an egalitarian and p ...

, which advocated for the overthrow of the Directory

Directory may refer to:

* Directory (computing), or folder, a file system structure in which to store computer files

* Directory (OpenVMS command)

* Directory service, a software application for organizing information about a computer network's u ...

and its replacement with a communist society

In Marxist thought, a communist society or the communist system is the type of society and economic system postulated to emerge from technological advances in the productive forces, representing the ultimate goal of the political ideology of co ...

. In his ''Manifesto of the Equals'' (1796), the proto-anarchist thinker Sylvain Maréchal demanded "the communal enjoyment of the fruits of the earth" and looked forward to the disappearance of "the revolting distinction of rich and poor, of great and small, of masters and valets, of governors and governed." The Conspiracy's attempt to overthrow the Directory failed and its leader François-Noël Babeuf

François-Noël Babeuf (; 23 November 1760 – 27 May 1797), also known as Gracchus Babeuf, was a French proto-communist, revolutionary, and journalist of the French Revolutionary period. His newspaper ''Le tribun du peuple'' (''The Tribune of ...

was executed by guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at t ...

, but their ideas carried on into the 19th century. Following the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

and the restoration of monarchy, socialist and anarchist ideas inspired by the ''Enragés'' and ''Equals'' began to replace republican ideals, setting up a new framework for French radicalism that began to reach an apex during the time of the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 F ...

.

From the Second Republic to the Jura Federation

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

(1809–1865) was the first philosopher to label himself an "anarchist.""Anarchism"BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

program, In Our Time, Thursday December 7, 2006. Hosted by Melvyn Bragg of the BBC, with John Keane, Professor of Politics at University of Westminster

The University of Westminster is a public university, public university based in London, United Kingdom. Founded in 1838 as the Royal Polytechnic Institution, it was the first Polytechnic (United Kingdom), polytechnic to open in London. The Polyte ...

, Ruth Kinna, Senior Lecturer in Politics at Loughborough University, and Peter Marshall Peter Marshall may refer to:

Entertainment

* Peter Marshall (entertainer) (born 1926), American game show host of ''The Hollywood Squares'', 1966–1981

* Peter Marshall (author, born 1939) (1939–1972), British novelist whose works include ''Th ...

, philosopher and historian. Proudhon opposed government privilege that protects capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

, banking and land interests, and the accumulation or acquisition of property (and any form of coercion that led to it) which he believed hampers competition and keeps wealth in the hands of the few. Proudhon favoured a right of individuals to retain the product of their labor as their own property, but believed that any property beyond that which an individual produced and could possess was illegitimate. Thus, he saw private property as both essential to liberty and a road to tyranny, the former when it resulted from labor and was required for labor and the latter when it resulted in exploitation (profit, interest, rent, tax). He generally called the former "possession" and the latter "property." For large-scale industry, he supported workers associations to replace wage labour and opposed the ownership of land.

Proudhon maintained that those who labor should retain the entirety of what they produce, and that monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

on credit and land are the forces that prohibit such. He advocated an economic system that included private property as possession and exchange market but without profit, which he called mutualism. It is Proudhon's philosophy that was explicitly rejected by Joseph Déjacque in the inception of anarchist-communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains re ...

, with the latter asserting directly to Proudhon in a letter that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature."

An early anarchist communist was

An early anarchist communist was Joseph Déjacque

Joseph Déjacque (; 27 December 1821, in Paris – 1864, in Paris) was a French early anarcho-communist poet, philosopher and writer. He coined the term "libertarian" (French: ''libertaire'') for himselfJoseph DéjacqueDe l'être-humain mâle ...

, the first person to describe himself as " libertaire".Joseph DéjacqueDe l'être-humain mâle et femelle - Lettre à P.J. Proudhon par Joseph Déjacque

(in French) Unlike

Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Soci ...

, he argued that, "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature." According to the anarchist historian Max Nettlau, the first use of the term libertarian communism was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to more clearly identify its doctrines. The French anarchist journalist Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

, later founder and editor of the four-volume ''Anarchist Encyclopedia,'' started the weekly paper ''Le Libertaire'' (''The Libertarian'') in 1895.

Déjacque was a major critic of Proudhon. Déjacque thought that "the Proudhonist version of Ricardian socialism

Ricardian socialism is a branch of classical economic thought based upon the work of the economist David Ricardo (1772–1823). The term is used to describe economists in the 1820s and 1830s who developed a theory of capitalist exploitation from ...

, centred on the reward of labour power and the problem of exchange value. In his polemic with Proudhon on women’s emancipation, Déjacque urged Proudhon to push on ‘as far as the abolition of the contract, the abolition not only of the sword and of capital, but of property and authority in all their forms,’ and refuted the commercial and wages logic of the demand for a ‘fair reward’ for ‘labour’ (labour power). Déjacque asked: ‘Am I thus... right to want, as with the system of contracts, to measure out to each — according to their accidental capacity to produce — what they are entitled to?’ The answer given by Déjacque to this question is unambiguous: ‘it is not the product of his or her labour that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature.’"...For Déjacque, on the other hand, the communal state of affairs — the phalanstery ‘without any hierarchy, without any authority’ except that of the ‘statistics book’ — corresponded to ‘natural exchange,’ i.e. to the ‘unlimited freedom of all production and consumption; the abolition of any sign of agricultural, individual, artistic or scientific property; the destruction of any individual holding of the products of work; the demonarchisation and the demonetarisation of manual and intellectual capital as well as capital in instruments, commerce and buildings.

Déjacque "rejected Blanquism

Blanquism refers to a conception of revolution generally attributed to Louis Auguste Blanqui (1805–1881) which holds that socialist revolution should be carried out by a relatively small group of highly organised and secretive conspirators. Ha ...

, which was based on a division between the ‘disciples of the great people’s Architect’ and ‘the people, or vulgar herd,’ and was equally opposed to all the variants of social republicanism, to the dictatorship of one man and to ‘the dictatorship of the little prodigies of the proletariat.’ With regard to the last of these, he wrote that: ‘a dictatorial committee composed of workers is certainly the most conceited and incompetent, and hence the most anti-revolutionary, thing that can be found...(It is better to have doubtful enemies in power than dubious friends)’. He saw ‘anarchic initiative,’ ‘reasoned will’ and ‘the autonomy of each’ as the conditions for the social revolution of the proletariat, the first expression of which had been the barricades of June 1848. In Déjacque's view, a government resulting from an insurrection remains a reactionary fetter on the free initiative of the proletariat. Or rather, such free initiative can only arise and develop by the masses ridding themselves of the ‘authoritarian prejudices’ by means of which the state reproduces itself in its primary function of representation and delegation. Déjacque wrote that: ‘By government I understand all delegation, all power outside the people,’ for which must be substituted, in a process whereby politics is transcended, the ‘people in direct possession of their sovereignty,’ or the ‘organised commune.’ For Déjacque, the communist anarchist utopia would fulfil the function of inciting each proletarian to explore his or her own human potentialities, in addition to correcting the ignorance of the proletarians concerning ‘social science.’"

After the creation of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

, or International Workingmen's Association (IWA) in London in 1864, Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

made his first tentative of creation an anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarianism is opposition to authoritarianism, which is defined as "a form of social organisation characterised by submission to authority", "favoring complete obedience or subjection to authority as opposed to individual freedom" an ...

revolutionary organization, the "International Revolutionary Brotherhood" ("Fraternité internationale révolutionnaire") or the Alliance ("l'Alliance"). He renewed this in 1868, creating the "International Brothers" ("Frères internationaux") or "Alliance for Democratic Socialism".

Bakunin and other federalists were excluded by Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

from the IWA at the Hague Congress of 1872, and formed the Jura Federation

The Jura Federation represented the anarchist, Bakuninist faction of the First International during the anti-statist split from the organization. Jura, a Swiss area, was known for its watchmaker artisans in La Chaux-de-Fonds, who shared anti- ...

, which met the next year at the 1872 Saint-Imier Congress, where was created the Anarchist St. Imier International

The Anarchist International of St. Imier was an international workers' organization formed in 1872 after the split in the First International between the anarchists and the Marxists. This followed the 'expulsions' of Mikhail Bakunin and James Gu ...

(1872–1877).

Anarchist participation in the Paris Commune

In 1870Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary s ...

led a failed uprising in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, third-largest city and Urban area (France), second-largest metropolitan area of F ...

on the principles later exemplified by the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

, calling for a general uprising in response to the collapse of the French government during the Franco-Prussian War, seeking to transform an imperialist conflict into social revolution. In his ''Letters to A Frenchman on the Present Crisis'', he argued for a revolutionary alliance between the working class and the peasantry and set forth his formulation of what was later to become known as propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pr ...

.

Anarchist historian George Woodcock

George Woodcock (; May 8, 1912 – January 28, 1995) was a Canadian writer of political biography and history, an anarchist thinker, a philosopher, an essayist and literary critic. He was also a poet and published several volumes of travel wri ...

reports that "The annual Congress of the International had not taken place in 1870 owing to the outbreak of the Paris Commune, and in 1871 the General Council called only a special conference in London. One delegate was able to attend from Spain and none from Italy, while a technical excuse - that they had split away from the Fédération Romande - was used to avoid inviting Bakunin's Swiss supporters. Thus only a tiny minority of anarchists was present, and the General Council's resolutions passed almost unanimously. Most of them were clearly directed against Bakunin and his followers."George Woodcock

George Woodcock (; May 8, 1912 – January 28, 1995) was a Canadian writer of political biography and history, an anarchist thinker, a philosopher, an essayist and literary critic. He was also a poet and published several volumes of travel wri ...

, '' Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements'' (1962). In 1872, the conflict climaxed with a final split between the two groups at the Hague Congress, where Bakunin and James Guillaume

James Guillaume (February 16, 1844, London – November 20, 1916, Paris) was a leading member of the Jura federation, the anarchist wing of the First International. Later, Guillaume would take an active role in the founding of the Anarchist St. I ...

were expelled from the International and its headquarters were transferred to New York. In response, the federalist sections formed their own International at the St. Imier Congress, adopting a revolutionary anarchist program.Robert Graham''Anarchism''

(Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2005) .

The

The Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

was a government that briefly ruled Paris from March 18 (more formally, from March 28) to May 28, 1871. The Commune was the result of an uprising in Paris after France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. Anarchists participated actively in the establishment of the Paris Commune. They included Louise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 – 9 January 1905) was a teacher and important figure in the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she embraced anarchism. When returning to France she emerged as an important French a ...

, the Reclus brothers, and Eugène Varlin

Eugène Varlin (; 5 October 1839 – 28 May 1871) was a French socialist, anarchist, communard and member of the First International. He was one of the pioneers of French syndicalism.

Biography Early life and activism

Louis-Eugène Varlin was ...

(the latter murdered in the repression afterwards). As for the reforms initiated by the Commune, such as the re-opening of workplaces as co-operatives, anarchists can see their ideas of associated labour beginning to be realised...Moreover, the Commune's ideas on federation obviously reflected the influence of Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Soci ...

on French radical ideas. Indeed, the Commune's vision of a communal France based on a federation of delegates bound by imperative mandates issued by their electors and subject to recall at any moment echoes Bakunin's and Proudhon's ideas (Proudhon, like Bakunin, had argued in favour of the "implementation of the binding mandate" in 1848...and for federation of communes). Thus both economically and politically the Paris Commune was heavily influenced by anarchist ideas.". George Woodcock manifests that "a notable contribution to the activities of the Commune and particularly to the organization of public services was made by members of various anarchist factions, including the mutualists Courbet, Longuet, and Vermorel, the libertarian collectivists

Collectivist anarchism, also called anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, Buckley, A. M. (2011). ''Anarchism''. Essential Libraryp. 97 "Collectivist anarchism, also called anarcho-collectivism, arose after mutualism." . is an anarchis ...

Varlin, Malon, and Lefrangais, and the bakuninists Elie and Élisée Reclus

Jacques Élisée Reclus (; 15 March 18304 July 1905) was a French geographer, writer and anarchist. He produced his 19-volume masterwork, ''La Nouvelle Géographie universelle, la terre et les hommes'' ("Universal Geography"), over a period of ...

and Louise Michel."

Louise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 – 9 January 1905) was a teacher and important figure in the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she embraced anarchism. When returning to France she emerged as an important French a ...

was an important anarchist participant in the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

. Initially she workerd as an ambulance woman, treating those injured on the barricades. During the Siege of Paris she untiringly preached resistance to the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

ns. On the establishment of the Commune, she joined the National Guard. She offered to shoot Thiers, and suggested the destruction of Paris by way of vengeance for its surrender.

In December 1871, she was brought before the 6th council of war, charged with offences including trying to overthrow the government, encouraging citizens to arm themselves, and herself using weapons and wearing a military uniform. Defiantly, she vowed to never renounce the Commune, and dared the judges to sentence her to death.Louise Michel, a French anarchist women who fought in the Paris communeReportedly, Michel told the court, "Since it seems that every heart that beats for freedom has no right to anything but a little slug of lead, I demand my share. If you let me live, I shall never cease to cry for vengeance." Following the 1871

Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended ...

, the anarchist movement, as the whole of the workers' movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

, was decapitated and deeply affected for years.

The propaganda of the deed period and exile to Britain

Parts of the anarchist movement, based in Switzerland, started theorizingpropaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pr ...

. From the late 1880s to 1895, a series of attacks by self-declared anarchists brought anarchism into the public eye and generated a wave of anxieties. The most infamous of these deeds were the bombs of Ravachol

François Claudius Koenigstein, also known as Ravachol, (14 October 1859 – 11 July 1892) was a French anarchist. He was born on 14 October 1859, at Saint-Chamond, Loire and died by being guillotined on 11 July 1892, at Montbrison, Loire, Montb ...

, Emile Henry, and Auguste Vaillant

Auguste Vaillant (27 December 1861 – 5 February 1894) was a French anarchist, most famous for his bomb attack on the French Chamber of Deputies on 9 December 1893. The government's reaction to this attack was the passing of the infamous repre ...

, and the assassination of the President of the Republic Sadi Carnot by Caserio.

After Auguste Vaillant

Auguste Vaillant (27 December 1861 – 5 February 1894) was a French anarchist, most famous for his bomb attack on the French Chamber of Deputies on 9 December 1893. The government's reaction to this attack was the passing of the infamous repre ...

's bomb in the Chamber of Deputies, the "Opportunist Republicans

The Moderates or Moderate Republicans (french: Républicains modérés), pejoratively labeled Opportunist Republicans (), was a French political group active in the late 19th century during the Third French Republic. The leaders of the group in ...

" voted in 1893 the first anti-terrorist laws, which were quickly denounced as ''lois scélérates

The ''lois scélérates'' ("villainous laws") – a pejorative name – were a set of three History of France, French laws passed from 1893 to 1894 under the French Third Republic, Third Republic (1870–1940) that restricted the 1881 freedom of th ...

'' ("villainous laws"). These laws severely restricted freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

. The first one condemned apology of any felony or crime as a felony itself, permitting widespread censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

of the press. The second one allowed to condemn any person directly or indirectly involved in a ''propaganda of the deed'' act, even if no killing was effectively carried on. The last one condemned any person or newspaper using anarchist propaganda (and, by extension, socialist libertarians present or former members of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA)):

"1. Either by provocation or by apology... nyone who hasencouraged one or several persons in committing either a stealing, or the crimes of murder, looting or arson...; 2. Or has addressed a provocation to military from the Army or the Navy, in the aim of diverting them from their military duties and the obedience due to their chiefs... will be deferred before courts and punished by a prison sentence of three months to two years.Thus,

free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

and encouraging propaganda of the deed or antimilitarism

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (espec ...

was severely restricted. Some people were condemned to prison for rejoicing themselves of the 1894 assassination of French president Sadi Carnot by the Italian anarchist Caserio. The term of ''lois scélérates'' ("villainous laws") has since entered popular language to design any harsh or injust laws, in particular anti-terrorism legislation which often broadly represses the whole of the social movements.

The United Kingdom quickly became the last haven for political refugees, in particular anarchists, who were all conflated with the few who had engaged in bombings. Already, the First International had been founded in London in 1871, where

The United Kingdom quickly became the last haven for political refugees, in particular anarchists, who were all conflated with the few who had engaged in bombings. Already, the First International had been founded in London in 1871, where Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

had taken refuge nearly twenty years before. But in the 1890s, the UK became a nest for anarchist colonies expelled from the continent, in particular between 1892 and 1895, which marked the height of the repression, with the " Trial of the Thirty" taking place in 1884. Louise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 – 9 January 1905) was a teacher and important figure in the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she embraced anarchism. When returning to France she emerged as an important French a ...

, a.k.a. "the Red Virgin", Émile Pouget

Émile Pouget (12 October 1860 in Pont-de-Salars, Aveyron, now Lozère – 21 July 1931 Palaiseau, Essonne) was a French anarcho-communist,The Anarchist Papers III, page 97 who adopted tactics close to those of anarcho-syndicalism. He was vice-se ...

or Charles Malato

Charles Malato (1857–1938) was a French anarchist and writer.

He was born to a noble Neapolitan family, his grandfather Count Malato being a Field Marshal and the Commander-in-Chief of the army of the last King of Naples. Though Count Malat ...

were the most famous of the many, anonymous anarchists, deserters

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which a ...

or simple criminals who had fled France and other European countries. Many of them returned to France after President Félix Faure

Félix François Faure (; 30 January 1841 – 16 February 1899) was the President of France from 1895 until his death in 1899. A native of Paris, he worked as a tanner in his younger years. Faure became a member of the Chamber of Deputies for ...

's amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offici ...

in February 1895. A few hundreds persons related to the anarchist movement would however remain in the UK between 1880 and 1914. The right of asylum was a British tradition since the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

in the 16th century. However, it would progressively be eroded, and the French immigrants were met with hostility. Several hate campaigns would be issued in the British press in the 1890s against these French exilees, relayed by riots and a "restrictionist" party which advocated the end of liberality concerning freedom of movement, and hostility towards French and international activists.

1895–1914

''Le Libertaire

''Le Libertaire'' is a Francophone anarchist newspaper established in New York City in June 1858 by the exiled anarchist Joseph Déjacque. It appeared at slightly irregular intervals until February 1861. The title reappeared in Algiers in 1892 a ...

'', a newspaper created by Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

, one of the leading supporters of Alfred Dreyfus, and Louise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 – 9 January 1905) was a teacher and important figure in the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she embraced anarchism. When returning to France she emerged as an important French a ...

, alias "The Red Virgin", published its first issue on November 16, 1895. The Confédération générale du travail

The General Confederation of Labour (french: Confédération Générale du Travail, CGT) is a national trade union center, founded in 1895 in the city of Limoges. It is the first of the five major French confederations of trade unions.

It is ...

(CGT) trade-union was created in the same year, from the fusion of the various "Bourses du Travail

The Bourse du Travail (French for "labour exchanges"), a French form of the labour council, were working class organizations that encouraged mutual aid, education, and self-organization amongst their members in the late nineteenth and earl ...

" (Fernand Pelloutier

Fernand-Léonce-Émile Pelloutier (1 October 1867, in Paris – 13 March 1901, in Sèvres) was a French anarchist and syndicalist.

He was the leader of the ''Bourses du Travail'', a major French trade union, from 1895 until his death in 1901. H ...

), the unions and the industries' federations. Dominated by anarcho-syndicalists

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in ...

, the CGT adopted the Charte d'Amiens in 1906, a year after the unification of the other socialist tendencies in the SFIO

The French Section of the Workers' International (french: Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO) was a list of political parties in France, political party in France that was founded in 1905 and succeeded in 1969 by the modern-da ...

party (French Section of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

) led by Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

and Jules Guesde

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter ...

.

Only eight French delegates attended the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam

The International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam took place from 24 August to 31 August 1907. It gathered delegates from 14 countries, among which important figures of the anarchist movement, including Errico Malatesta, Luigi Fabbri, Benoît B ...

in August 1907. According to historian Jean Maitron

Jean Maitron (17 December 1910 – 16 November 1987) was a French historian specialist of the labour movement. A pioneer of such historical studies in France, he introduced it to University and gave it its archives base, by creating in 1949 the '' ...

, the anarchist movement in France was divided into those who rejected the sole idea of organisation, and were therefore opposed to the very idea of an international organisation, and those who put all their hopes in syndicalism

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of prod ...

, and thus "were occupied elsewhere".Jean Maitron

Jean Maitron (17 December 1910 – 16 November 1987) was a French historian specialist of the labour movement. A pioneer of such historical studies in France, he introduced it to University and gave it its archives base, by creating in 1949 the '' ...

, ''Le mouvement anarchiste en France'', tome I, Tel Gallimard (François Maspero

François Maspero (19 January 1932, in Paris – 11 April 2015, in Paris) was a French author and journalist, best known as a publisher of leftist books in the 1970s. He also worked as a translator, translating the works of Joseph Conrad, Mehdi B ...

, 1975), pp.443-445 Only eight French anarchists assisted the Congress, among whom Benoît Broutchoux

Benedict Broutchoux (7 November 1879 – 2 June 1944) was a French anarchist opposed to the reformist Émile Basly during a strike in the north of France, in 1902.

Further reading

*

* Phil Casoar, Stéphane Callens, ''Les aventures � ...

, Pierre Monatte

Pierre Monatte (15 January 188127 June 1960) was a French trade unionist, a founder of the ''Confédération générale du travail'' (CGT, Generation Confederation of Labour) at the beginning of the 20th century, and founder of its journal '' La ...

and René de Marmande.

A few tentatives of organisation followed the Congress, but all were short-lived. In the industrial North, anarchists from Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France region, the prefecture of the N ...

, Armentières, Denains, Lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements ...

, Roubaix

Roubaix ( or ; nl, Robaais; vls, Roboais) is a city in northern France, located in the Lille metropolitan area on the Belgian border. It is a historically mono-industrial commune in the Nord department, which grew rapidly in the 19th century ...

and Tourcoing

Tourcoing (; nl, Toerkonje ; vls, Terkoeje; pcd, Tourco) is a city in northern France on the Belgian border. It is designated municipally as a commune within the department of Nord. Located to the north-northeast of Lille, adjacent to Roubai ...

decided to call for a Congress in December 1907, and agreed upon the creation of a newspaper, '' Le Combat'', which editorial board was to act as the informal bureau of an officially non-existent federation. Another federation was created in the Seine and the Seine-et-Oise

Seine-et-Oise () was the former department of France encompassing the western, northern and southern parts of the metropolitan area of Paris.Jean Maitron

Jean Maitron (17 December 1910 – 16 November 1987) was a French historian specialist of the labour movement. A pioneer of such historical studies in France, he introduced it to University and gave it its archives base, by creating in 1949 the '' ...

, 1975, tome I, p.446

However, at the approach of the 1910 legislative election, an Anti-Parliamentary Committee was set up and, instead of dissolving itself afterwards, became permanent under the name of Alliance communiste anarchiste (Communist Anarchist Alliance). The new organisation excluded any permanent members.

However, at the approach of the 1910 legislative election, an Anti-Parliamentary Committee was set up and, instead of dissolving itself afterwards, became permanent under the name of Alliance communiste anarchiste (Communist Anarchist Alliance). The new organisation excluded any permanent members.Jean Maitron

Jean Maitron (17 December 1910 – 16 November 1987) was a French historian specialist of the labour movement. A pioneer of such historical studies in France, he introduced it to University and gave it its archives base, by creating in 1949 the '' ...

, 1975, tome I, p.448 Although this new group also faced opposition from certain anarchists (including Jean Grave

Jean Grave (; October 16, 1854, Le Breuil-sur-Couze – December 8, 1939, Vienne-en-Val) was an important activist in the French anarchist and the international anarchist communism movements. He was the editor of three major anarchist periodica ...

), it was quickly replaced by a new organization, the Fédération communiste (Communist Federation).

The Communist Federation was founded in June 1911 with 400 members, all from the Parisian region. It quickly took the name of Fédération anarcho-communiste (Anarcho-Communist Federation), choosing Louis Lecoin as secretary. The Fédération communiste révolutionnaire anarchiste, headed by Sébastien Faure

Sébastien Faure (6 January 1858 – 14 July 1942) was a French anarchist, freethought and secularist activist and a principal proponent of synthesis anarchism.

Biography

Before becoming a free-thinker, Faure was a seminarist. He engage ...

, succeeded to the FCA in August 1913.

The French anarchist milieu also included many individualists. They centered around publications such as ''L'Anarchie

''L'Anarchie'' (, ''anarchy'') was a French individualist anarchist journal established in April 1905 by Albert Libertad. Along with Libertad, contributors to the journal included Émile Armand, André Lorulot, Émilie Lamotte, Raymond Callemi ...

'' and '' L'En-Dehors''. The main French individualist anarchist theorists were Émile Armand

Émile Armand (26 March 1872 – 19 February 1962), pseudonym of Ernest-Lucien Juin Armand, was an influential French individualist anarchist at the beginning of the 20th century and also a dedicated free love/polyamory, intentional community, a ...

and Han Ryner who also were influential in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

. Other important individualist activists included Albert Libertad

Joseph Albert (known as Albert Libertad or Libertad) (24 November 1875 – 12 November 1908) was an individualist anarchist militant and writer from France who edited the influential anarchist publication ''L'Anarchie''.

Life and work

He was born ...

, André Lorulot

André Lorulot (born Georges André Roulot; 23 October 1885 – 11 March 1963) was a French individualist anarchist and freethinker

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs shou ...

, Victor Serge

Victor Serge (; 1890–1947), born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich (russian: Ви́ктор Льво́вич Киба́льчич), was a Russian revolutionary Marxist, novelist, poet and historian. Originally an anarchist, he joined the Bolsheviks fi ...

, Zo d'Axa

Alphonse Gallaud de la Pérouse (28 May 1864 – 30 August 1930), better known as Zo d'Axa (), was a French adventurer, anti-militarist, satirist, journalist, and founder of two of the most legendary French magazines, ''L' EnDehors'' and ''La Feui ...

and Rirette Maîtrejean. Influenced by Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

's egoism

Egoism is a philosophy concerned with the role of the self, or , as the motivation and goal of one's own action. Different theories of egoism encompass a range of disparate ideas and can generally be categorized into descriptive or normativ ...

and the criminal/political exploits of Clément Duval

Clément Duval (; 1850–1935) was a famous French anarchist and criminal. His ideas concerning individual reclamation were greatly influential in later shaping illegalism. According to Paul Albert, "The story of Clement Duval was lifted and, sho ...

and Marius Jacob

Alexandre Marius Jacob (September 29, 1879 – August 28, 1954), also known by the names Georges, Escande, Férau, Jean Concorde, Attila, and Barrabas, was a French anarchist illegalist.

Biography

Jacob was born in 1879 in Marseille to a work ...

, France became the birthplace of illegalism

Illegalism is a tendency of anarchism that developed primarily in France, Italy, Belgium and Switzerland during the late 1890s and early 1900s as an outgrowth of individualist anarchism. Illegalists embrace criminality either openly or secretly ...

, a controversial anarchist ideology that openly embraced criminality.

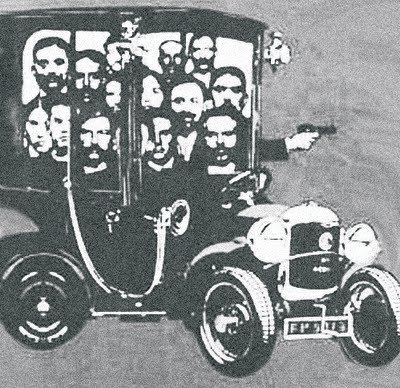

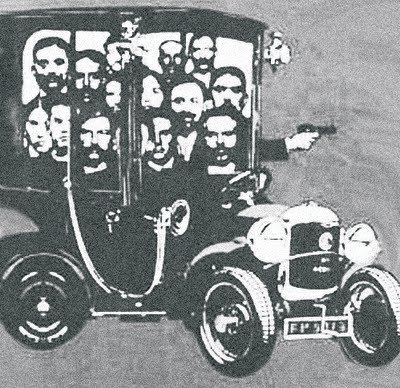

Relations between individualist and communist anarchists remained poor throughout the pre-war years. Following the 1913 trial of the infamous Bonnot Gang, the FCA condemned individualism as bourgeois and more in keeping with capitalism than communism. An article believed to have been written by Peter Kropotkin, in the British anarchist paper '' Freedom'', argued that "Simple-minded young comrades were often led away by the illegalists' apparent anarchist logic; outsiders simply felt disgusted with anarchist ideas and definitely stopped their ears to any propaganda."

After the assassination of anti-militarist

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (esp ...

socialist leader Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

a few days before the beginning of World War I, and the subsequent rallying of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

and the workers' movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

to the war, even some anarchists supported the Sacred Union (Union Sacrée The Sacred Union (french: Union Sacrée, ) was a political truce in France in which the left-wing agreed, during World War I, not to oppose the government or call any strikes. Made in the name of patriotism, it stood in opposition to the pledge mad ...

) government. Jean Grave

Jean Grave (; October 16, 1854, Le Breuil-sur-Couze – December 8, 1939, Vienne-en-Val) was an important activist in the French anarchist and the international anarchist communism movements. He was the editor of three major anarchist periodica ...

, Peter Kropotkin and others published the ''Manifesto of the Sixteen

The ''Manifesto of the Sixteen'' (french: Manifeste des seize), or ''Proclamation of the Sixteen'', was a document drafted in 1916 by eminent anarchists Peter Kropotkin and Jean Grave which advocated an Allied victory over Germany and the Cen ...

'' supporting the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

against Germany. A clandestine issue of the ''Libertaire'' was published on June 15, 1917.

French individualist anarchism

Anarchist Manifesto

''Anarchist Manifesto'' (or ''The World's First Anarchist Manifesto'') is a work by Anselme Bellegarrigue, notable for being the first manifesto of anarchism. It was written in 1850, two years after his participation in the French Revolution o ...

in 1850. Catalan historian of individualist anarchism Xavier Diez reports that during his travels in the United States "he at least contacted (Henry David) Thoreau and, probably (Josiah) Warren."''Autonomie Individuelle'' was an individualist anarchist publication that ran from 1887 to 1888. It was edited by Jean-Baptiste Louiche, Charles Schæffer and Georges Deherme.

Later, this tradition continued with such intellectuals as Albert Libertad

Joseph Albert (known as Albert Libertad or Libertad) (24 November 1875 – 12 November 1908) was an individualist anarchist militant and writer from France who edited the influential anarchist publication ''L'Anarchie''.

Life and work

He was born ...

, André Lorulot

André Lorulot (born Georges André Roulot; 23 October 1885 – 11 March 1963) was a French individualist anarchist and freethinker

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs shou ...

, Émile Armand

Émile Armand (26 March 1872 – 19 February 1962), pseudonym of Ernest-Lucien Juin Armand, was an influential French individualist anarchist at the beginning of the 20th century and also a dedicated free love/polyamory, intentional community, a ...

, Victor Serge

Victor Serge (; 1890–1947), born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich (russian: Ви́ктор Льво́вич Киба́льчич), was a Russian revolutionary Marxist, novelist, poet and historian. Originally an anarchist, he joined the Bolsheviks fi ...

, Zo d'Axa

Alphonse Gallaud de la Pérouse (28 May 1864 – 30 August 1930), better known as Zo d'Axa (), was a French adventurer, anti-militarist, satirist, journalist, and founder of two of the most legendary French magazines, ''L' EnDehors'' and ''La Feui ...

and Rirette Maîtrejean, who developed theory in the main individualist anarchist journal in France, ''L'Anarchie

''L'Anarchie'' (, ''anarchy'') was a French individualist anarchist journal established in April 1905 by Albert Libertad. Along with Libertad, contributors to the journal included Émile Armand, André Lorulot, Émilie Lamotte, Raymond Callemi ...

'' in 1905. Outside this journal, Han Ryner wrote ''Petit Manuel individualiste'' (1903). Later appeared the journal '' L'En-Dehors'' created by Zo d'Axa in 1891.

French individualist circles had a strong sense of personal libertarianism and experimentation. Naturism and

French individualist circles had a strong sense of personal libertarianism and experimentation. Naturism and free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

contents started to have an influence in individualist anarchist circles and from there it expanded to the rest of anarchism also appearing in Spanish individualist anarchist groups. "Along with feverish activity against the social order, (Albert) Libertad was usually also organizing feasts, dances and country excursions, in consequence of his vision of anarchism as the “joy of living

''Joy of Living'' is a 1938 American musical comedy film directed by Tay Garnett and starring Irene Dunne and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. with supporting performances from Alice Brady, Guy Kibbee, Jean Dixon, Eric Blore and Lucille Ball. It features ...

” and not as militant sacrifice and death instinct, seeking to reconcile the requirements of the individual (in his need for autonomy) with the need to destroy authoritarian society."

Anarchist naturism was promoted by Henri Zisly

Henri Zisly (born in Paris, 2 November 1872; died in 1945)

was a French

Illegalism

Illegalism

, by Doug Imrie (published by '' Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed'') is an anarchist philosophy that developed primarily in France, Italy, Belgium, and Switzerland during the early 1900s as an outgrowth of Stirner's individualist anarchism."Parallel to the social, collectivist anarchist current there was an individualist one whose partisans emphasized their individual freedom and advised other individuals to do the same. Individualist anarchist activity spanned the full spectrum of alternatives to authoritarian society, subverting it by undermining its way of life facet by facet."Thus theft, counterfeiting, swindling and robbery became a way of life for hundreds of individualists, as it was already for countless thousands of proletarians. The wave of anarchist bombings and assassinations of the 1890s (Auguste Vaillant, Ravachol, Emile Henry, Sante Caserio) and the practice of illegalism from the mid-1880s to the start of the First World War (Clément Duval, Pini, Marius Jacob, the Bonnot gang) were twin aspects of the same proletarian offensive, but were expressed in an individualist practice, one that complemented the great collective struggles against capital." Illegalists usually did not seek moral basis for their actions, recognizing only the reality of "might" rather than "right"; for the most part, illegal acts were done simply to satisfy personal desires, not for some greater ideal,Parry, Richard. The Bonnot Gang. Rebel Press, 1987. p. 15 although some committed crimes as a form of

"Illegalism" by Rob los Ricos

in what is known as

was a French

Émile Gravelle

Émile Gravelle (1855–1920) was a French individualist anarchist and naturist activist, writer and painter.Etudes Jean-Jacques Rousseau Musée Jean-Jacques Rousseau - 1996 Le fondateur du Naturianisme est Émile Gravelle. Né en 1855 à Doua ...

and Georges Butaud. Butaud was an individualist "partisan of the '' milieux libres'', publisher of "Flambeau" ("an enemy of authority") in 1901 in Vienna. Most of his energies were devoted to creating anarchist colonies (communautés expérimentales) in which he participated in several.

"In this sense, the theoretical positions and the vital experiences of french individualism are deeply iconoclastic and scandalous, even within libertarian circles. The call of nudist naturism, the strong defence of birth control methods, the idea of " unions of egoists" with the sole justification of sexual practices, that will try to put in practice, not without difficulties, will establish a way of thought and action, and will result in sympathy within some, and a strong rejection within others.""La insumisión voluntaria. El anarquismo individualista español durante la dictadura y la Segunda República" by Xavier DíezIllegalism

Illegalism

Illegalism, by Doug Imrie (published by '' Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed'') is an anarchist philosophy that developed primarily in France, Italy, Belgium, and Switzerland during the early 1900s as an outgrowth of Stirner's individualist anarchism."Parallel to the social, collectivist anarchist current there was an individualist one whose partisans emphasized their individual freedom and advised other individuals to do the same. Individualist anarchist activity spanned the full spectrum of alternatives to authoritarian society, subverting it by undermining its way of life facet by facet."Thus theft, counterfeiting, swindling and robbery became a way of life for hundreds of individualists, as it was already for countless thousands of proletarians. The wave of anarchist bombings and assassinations of the 1890s (Auguste Vaillant, Ravachol, Emile Henry, Sante Caserio) and the practice of illegalism from the mid-1880s to the start of the First World War (Clément Duval, Pini, Marius Jacob, the Bonnot gang) were twin aspects of the same proletarian offensive, but were expressed in an individualist practice, one that complemented the great collective struggles against capital." Illegalists usually did not seek moral basis for their actions, recognizing only the reality of "might" rather than "right"; for the most part, illegal acts were done simply to satisfy personal desires, not for some greater ideal,Parry, Richard. The Bonnot Gang. Rebel Press, 1987. p. 15 although some committed crimes as a form of

Propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pr ...

. The illegalists embraced direct action and propaganda by the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pr ...

.

Influenced by theorist Max Stirner's egoism

Egoism is a philosophy concerned with the role of the self, or , as the motivation and goal of one's own action. Different theories of egoism encompass a range of disparate ideas and can generally be categorized into descriptive or normativ ...

as well as Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Soci ...

(his view that Property is theft!

"Property is theft!" (french: La propriété, c'est le vol!) is a slogan coined by French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his 1840 book ''What Is Property? or, An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government''.

Overview

By "pro ...

), Clément Duval

Clément Duval (; 1850–1935) was a famous French anarchist and criminal. His ideas concerning individual reclamation were greatly influential in later shaping illegalism. According to Paul Albert, "The story of Clement Duval was lifted and, sho ...

and Marius Jacob

Alexandre Marius Jacob (September 29, 1879 – August 28, 1954), also known by the names Georges, Escande, Férau, Jean Concorde, Attila, and Barrabas, was a French anarchist illegalist.

Biography

Jacob was born in 1879 in Marseille to a work ...

proposed the theory of la ''reprise individuelle'' (Eng: individual reclamation

The following is a list of terms specific to anarchists. Anarchism is a political and social movement which advocates voluntary association in opposition to authoritarianism and hierarchy.

__NOTOC__

A

:The negation of rule or "government by no ...

) which justified robbery on the rich and personal direct action against exploiters and the system.,

Illegalism first rose to prominence among a generation of Europeans inspired by the unrest of the 1890s, during which Ravachol

François Claudius Koenigstein, also known as Ravachol, (14 October 1859 – 11 July 1892) was a French anarchist. He was born on 14 October 1859, at Saint-Chamond, Loire and died by being guillotined on 11 July 1892, at Montbrison, Loire, Montb ...

, Émile Henry, Auguste Vaillant

Auguste Vaillant (27 December 1861 – 5 February 1894) was a French anarchist, most famous for his bomb attack on the French Chamber of Deputies on 9 December 1893. The government's reaction to this attack was the passing of the infamous repre ...

, and Caserio committed daring crimes in the name of anarchism,"Pre-World War I France was the setting for the only documented anarchist revolutionary movement to embrace all illegal activity as revolutionary practice. Pick-pocketing, theft from the workplace, robbery, confidence scams, desertion from the armed forces, you name it, illegalist activity was praised as a justifiable and necessary aspect of class struggle"Illegalism" by Rob los Ricos

in what is known as

propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pr ...

. France's Bonnot Gang was the most famous group to embrace illegalism.

From World War I to World War II

After the war, the CGT became more reformist, and anarchists progressively drifted out. Formerly dominated by the anarcho-syndicalists, the CGT split into a non-communist section and a communist ''Confédération générale du travail unitaire

The Confédération générale du travail unitaire, or CGTU ( en, United General Confederation of Labor), was a trade union confederation in France that at first included anarcho-syndicalists and soon became aligned with the French Communist Par ...

'' (CGTU) after the 1920 Tours Congress

The Tours Congress was the 18th National Congress of the French Section of the Workers' International, or SFIO, which took place in Tours on 25–30 December 1920. During the Congress, the majority voted to join the Third International and create ...

which marked the creation of the French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Un ...

(PCF). A new weekly series of the ''Libertaire'' was edited, and the anarchists announced the imminent creation of an Anarchist Federation. A Union Anarchiste (UA) group was constituted in November 1919 against the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s, and the first daily issue of the ''Libertaire'' got out on December 4, 1923.

Russian exiles, among them Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

and Piotr Arshinov

Peter Andreyevich Arshinov (russian: Пётр Андре́евич Арши́нов; 1887–1937), was a Russian anarchist revolutionary and intellectual who chronicled the history of the Makhnovshchina.

Initially a Bolshevik, during the 1905 ...

, founded in Paris the review ''Dielo Truda

''The Cause of Labor'' (russian: Дело Труда, trans-lit=Delo Truda) was a libertarian communist magazine published by exiled Russian and Ukrainian anarchists. Initially under the editorship of Peter Arshinov, after it published the '' ...

'' (Дело Труда, ''The Cause of Labour'') in 1925. Makhno co-wrote and co-published ''The Organizational Platform of the Libertarian Communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

s'', which put forward ideas on how anarchists should organize based on the experiences of revolutionary Ukraine and the defeat at the hand of the Bolsheviks. The document was initially rejected by most anarchists, but today has a wide following. It remains controversial to this day, some (including, at the time of publication, Volin

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum (russian: Все́волод Миха́йлович Эйхенба́ум; 11 August 188218 September 1945), commonly known by his psuedonym Volin (russian: Во́лин), was a Russian anarchist intellectual. H ...

and Malatesta Malatesta may refer to:

People Given name

* Malatesta (I) da Verucchio (1212–1312), founder of the powerful Italian Malatesta family and a famous condottiero

* Malatesta IV Baglioni (1491–1531), Italian condottiero and lord of Perugia, Bettona, ...

) viewing its implications as too rigid and hierarchical. Platformism

Platformism is a form of anarchist organization that seeks unity from its participants, having as a defining characteristic the idea that each platformist organization should include only people that are fully in agreement with core group ideas, r ...

, as Makhno's position came to be known, advocated ideological unity, tactical unity, collective action and discipline, and federalism. Five hundred people attended Makhno's 1934 funeral at the Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (french: Cimetière du Père-Lachaise ; formerly , "East Cemetery") is the largest cemetery in Paris, France (). With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world. Notable figure ...

.

In June 1926, "The Organisational Platform Project for a General Union of Anarchists", best known under the name "Archinov's Platform", was launched. Volin responded by publishing a ''Synthesis'' project in his article "Le problème organisationnel et l'idée de synthèse" ("The Organisational Problem and the Idea of a Synthesis"). After the Orléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and Union anarchiste communiste). The gap widened between proponents of Platformism and those who followed Volin's

/ref> The OPB pushed for a move which saw the FA change its name into the Fédération communiste libertaire (FCL) after the 1953 Congress in Paris, while an article in ''Le Libertaire'' indicated the end of the cooperation with the French

During the events of May 1968 the anarchist groups active in France were

During the events of May 1968 the anarchist groups active in France were

http://cnt-ait.info

English section of the web site : * Libertarian Communist Organization (France) (OCL,

online

*Sonn, Richard D. ''Anarchism and Cultural Politics in Fin-de-Siècle France''. University of Nebraska Press. 1989. *Sonn, Richard D. '' Sex, Violence, and the Avant-Garde: Anarchism in Interwar France''. Penn State Press. 2010. *Varias, Alexander. ''Paris and the Anarchists''. New York. 1996.

Non Fides - anarchist portalFrancophone anarchist federationCNT France (Vignoles)CNT France (AIT)Radio Libertaire''Le Monde Libertaire''Cédric Guerin. "Pensée et action des anarchistes en France : 1950-1970"